Section 5: Tracking code with Git

I use version control for nearly all of the programming I do. It's a crucial skill for learning to how program that can fall by the wayside in favor of learning a specific programming language. Leaning to program and learning version control should happen side-by-side. But what is "version control?" Version control is more than just saving a file. Here's a description from the book Pro Git:

Version control is a system that records changes to a file or set of files over time so that you can recall specific versions later.

By preserving a history of incremental changes over time, you can go back and see what you've done, find out when and why something stopped working, make multiple changes to your project in parallel, and more. In this section, I'll introduce Git, a common tool for version control developed by Linus Torvalds.

TIP

This free book is the definitive resource for learning Git. I highly recommend skimming chapters 1-3.

How does git work?

At the core, Git records changes to your files over time. Unlike other systems that store differences between file versions, Git takes snapshots of your entire project each time you make a commit. These snapshots allow you to revisit any point in your project's history.

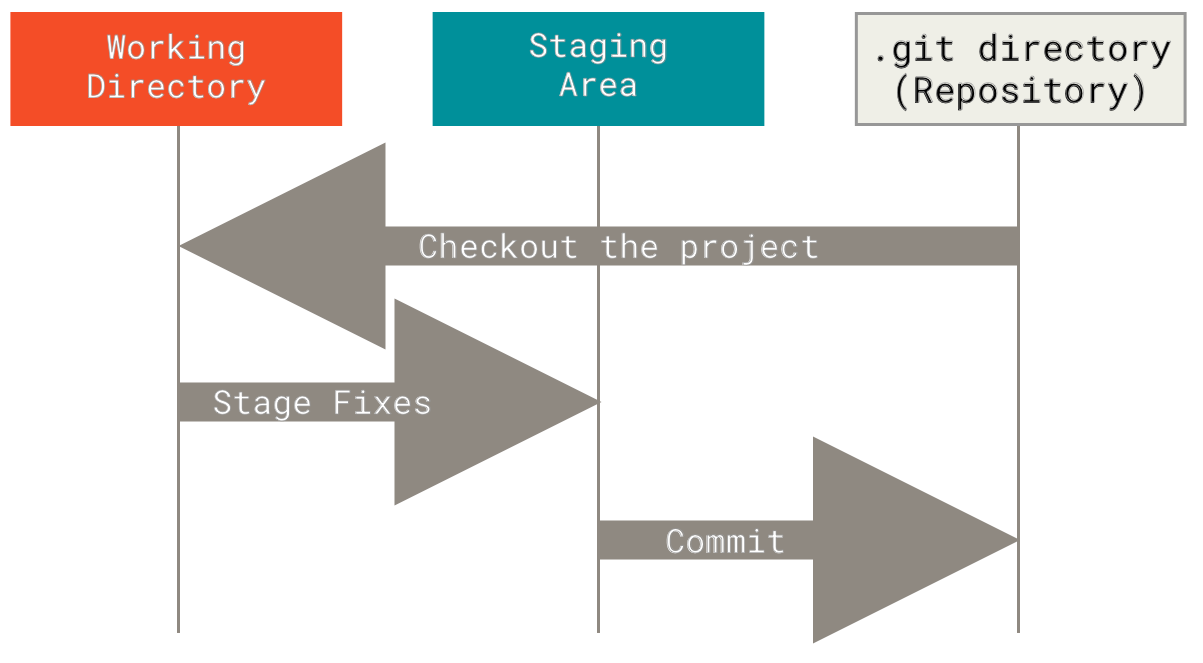

Here's a high-level overview of how git tracks your files:

Repository Initialization: When you initialize a Git repository in your project directory using

git init, Git starts monitoring the files within that directory.Working Directory and Staging Area: As you modify files, the changes are reflected in your 'working' directory. To prepare changes for a commit, you add them to the staging area using

git add. This step lets you decide which changes to include in your next snapshot.Committing Changes: After staging, you create a commit with

git commit. This action records a snapshot of the staged changes and adds it to your project's history. Each commit is uniquely identified, allowing you to track and revert to specific versions.Local and Remote Repositories: Git stores your project's history locally, but, optionally, you can also link your repository to a remote server like GitHub or Bitbucket which enables collaboration, backup, and access from different machines. I'll talk more about this in the next section.

Working tree, staging area, and Git directory taken from Pro Git

Basic git

To get started with Git, you'll need to familiarize yourself with a couple key commands:

Initialize a Repository:

You create a new Git repository by telling Git to start tracking the code in a directory.

mkdir my-project

cd my-project

git initOr, you can clone an existing Git repository from a remote server to your local machine.

git clone <repository URL>

cd my_projectTIP

A quick note about cloning a remote repository. There are several methods for doing this, some of which require a little set up, and those will be covered in the next section.

Check Repository Status:

After you've made some changes in your directory, you can check what these are using the following command.

git statusThis command displays the status of your working directory and staging area. It shows what file have been edited, what new files aren't being tracked, and more.

Add Changes to Staging Area:

git add [file(s)]Stages specific files for the next commit. Use git add . to stage all changes.

Commit Changes:

git commit -m "Your commit message"Records a snapshot of the staged changes. The commit message should briefly describe what you've done. It's important to write a good commit message.

View Commit History:

You can see a log of all commits that have been made to a project.

git logCompare Changes:

This can be useful, but you're unlikely to do it much.

git diffIt compares changes between commits, branches, or your working directory and the last commit.

Push Changes to Remote Repository:

git pushUploads your local commits to a remote repository.

Pull Updates from Remote Repository:

git pullFetches and merges updates from a remote repository into your local repository.

These commands form the backbone of Git operations. Regular use of git status and git log will help you stay informed about your project's state and history.

Branching and Merging

Branches are a powerful feature in Git that allow you to diverge from the main codebase and work independently on a set of changes. The primary branch is usually called main or sometimes master, and it's where the stable version of your project resides.

Why Use Branches?

Branching your code with Git allows for parallel development of multiple features or fixes simultaneously without interference. While you're editing the code on a branch, the main branch remains stable, and new code is only merged after it's ready. Here are some things you might use branches for:

Feature Development: When adding new features, you can create a branch to isolate your work. This way, the main codebase remains unaffected until the feature is complete and tested.

Bug Fixes: For fixing bugs, especially in a production environment, branches let you address issues without disrupting ongoing development work.

Experimentation: If you're trying out new ideas or approaches, branches provide a safe space to experiment without the risk of breaking existing code.

See all active branches:

If you want to see what branches you have active locally, run:

git branchThis will print out the branches you have in your local repo and tell you which branch you're currently on.

Switch to a Branch:

If you want to switch (or checkout) a different branch, run:

git checkout [branch-name]This switches your working directory to the specified branch.

Create and Switch to a New Branch:

To make a new branch, run:

git checkout -b [branch-name]This is a shortcut that creates a new branch and switches to it immediately.

Merge a Branch:

After you've completed work on a branch and ensured it's stable, you'll want to merge it back into the main branch. This process integrates your changes and updates the main codebase. First, checkout the branch you want to merge into:

git checkout [target-branch]Once you're in the target branch (for example, main), merge the branch with your changes by running:

git merge [source-branch]This merges the changes in the [source-branch] into [target-branch].

Note

While this approach works well for merging branches locally, in collaborative projects, you'll typically merge branches using pull requests. I'll cover this in more detail in the next section.